5 Seconds Of Summer are a boy band masquerading as a rock group: four cute white guys who sing generic love songs that teenage girls can imagine to be about themselves. Like all boy bands, their actual music comes a distant second to the parasocial relationship they seek the develop with their listeners, and their specific gimmick (all four members play their own instruments) is notable only in the way it invites comparison to the Monkees, who at least had the decency to hate themselves.

Their first batch of songs sounded like One Direction for budding rockists, but they quickly moved on to faux-rebellious Good Charlotte knock-offs before making a brief foray into socialist anthems that sound like Disney Channel bumper musical and finally settling on dreary, bloodless power-ballads that sound like nothing. An adult (or a more discerning teenager) encountering them for the first time would find them anywhere between mediocre and mildly irritating, yet they inspire the sort of slavish devotion reserved for serfs in Medieval Europe and sixteen-year-olds who use Twitter.

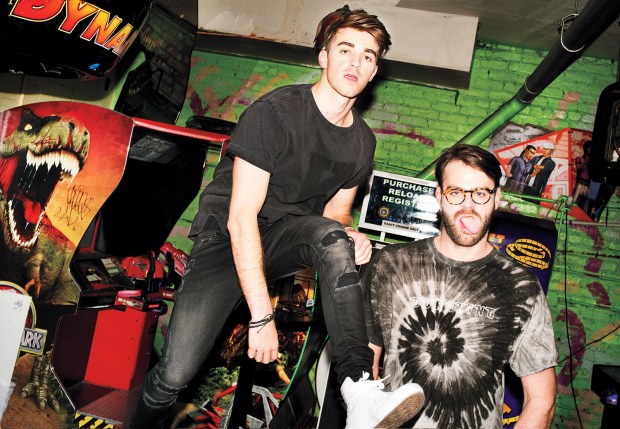

The Chainsmokers are ostensibly an EDM duo who have produced a handful of crossover pop hits, but they are more likely a deep-cover PSYOP meant to drive me insane and/or activate my programming as part of a Soviet sleeper cell — only time will tell. The Chainsmokers have collaborated with a lot of vocalists over the course of their career, but the majority of them are either up-and-coming singers just about to hit it big (what up Daya, what up Halsey) or unknowns who immediately retreat back into obscurity (shout-out Rozes, Waterbed, Victoria Zaro).

The new Chainsmokers song, “Who Do You Love (feat. 5 Seconds Of Summer)”, represents a break from the duo’s recent output in a few ways. For starters, it’s the first song they’ve released in nearly two years without any vocals from Drew – even “Side Effects,” Emily Warren’s moment in the spotlight, had him Drew’s voice buried somewhere in mix. But more importantly, “Who Do You Love” marks only the third time in their career that the Chainsmokers have worked with someone who was undeniably more famous than them. At first glance, this might not seem so strange – what group of self-respecting up-and-coming DJs with aspirations towards alt-rock stardom wouldn’t jump at the chance to raise their profile? It’s not difficult to see what the Chainsmokers stand to gain from these collaborations – but it’s a little harder to understand what, exactly, the other party stands to gain from doing a song with the guys who made “#SELFIE”?

That 5 Seconds Of Summer would want to work with the Chainsmokers makes a certain kind of cosmic sense: as we all know, the Chainsmokers rose to prominence off the back of a novelty song so firmly planted in the cultural milieu of the mid-2010’s that parents across the world will someday face the scorn of their collective offspring when the next generation discovers that we were lame enough to make this song a hit – that is, if the next generation isn’t totally wiped out by the impending climate apocalypse.

5 Seconds Of Summer, on the other hand, first became famous by performing passable acoustic covers of pop songs in their poorly-lit bedrooms. Both groups harnessed a sort of specifically online energy that didn’t exist five years prior, and they couldn’t have existed without it. If I were eschatologically inclined, I would say that their coming together is a momentous event, laden with mystical signs and portents, so indicative of shifting cultural tides that it potentially heralds the end of the world as we know it – but in reality, the only omen of that kind was the IPCC’s report stating that we only have twelve years to radically reduce emissions before the damage we’ve done to our planet becomes irreversible.

Sorry. That was the last one, I promise.

It would be easy enough to accept the party line on why the Chainsmokers and 5 Seconds Of Summer decided to work together – that they’re friends who have been looking for an opportunity to collaborate and finally found a song that worked – were it not for one small detail. It’s easy to miss, unless you comb over the song’s credits and spot the presence of an additional producer: one Warren “Oak” Felder, a songwriter and producer whose best known work, aside from his numerous collaborations with Kehlani and Alessia Cara, is “Sorry Not Sorry” by Demi Lovato, a transparently cynical attempt to play off a piece of internet slang that was already dated in 2017 which is, nonetheless, a pretty fun song.

In fact, in spite of the differences in mood and lyrical content, “Sorry Not Sorry” sounds surprisingly similar to “Who Do You Love”. The tempo is the same, the distorted piano in the opening verses are the same, as are the synth stabs in the chorus – even the multi-layered singing of the 5SOS boys resembles the call-and-response background vocals on “Sorry”. In fact, aside from the acoustic guitar/EDM drop in the chorus, there is very little in the new Chainsmokers song that bears the mark of the Chainsmokers themselves, especially considering that 5SOS have plenty of songs featuring acoustic guitar and the drop is, even by Chainsmokers standards, pretty light. To put it bluntly, if you are at all familiar with Felder’s work, it is easy to listen to this song and wonder just how much work the Chainsmokers actually did.

Before we go any further, I should get this on the record: I have never worked in the music industry in any capacity and have an extremely limited amount of knowledge regarding the songwriting and production process. My lack of understanding with regards to musical theory should be obvious by the fact that I have now spent a full year of my life thinking and writing about the Chainsmokers, but it still bears mentioning that I am not qualified to discern what elements of “Who Do You Love” were provided by the Chainsmokers and which were provided by 5SOS or by Warren Oak, and even if I could, that would not account for the mysterious and often untraceable process of artistic collaboration. I am only qualified to speak as an informed listener, but even with those scant qualifications, I can say with some confidence that 5 Seconds Of Summer and Warren Oak could have created this song, or a song so similar to this one as to be indistinguishable, entirely on their own. The question then, is: why didn’t they?

You could certainly argue that working with the Chainsmokers grants 5SOS some added exposure – after all, I hadn’t seriously thought about them for nearly four years, and now here I am, poisoning my brain by reading the comments on their YouTube videos. And it’s true that 5SOS have never scored a number-one single in America. But they’re still putting out multi-Platinum records five years after their debut, and they’re even more successful in their home country of Australia. They’re doing better than ever, honestly. Their career didn’t need a shot in the arm, and it certainly didn’t require them to take a gamble like collaborating with the Chainsmokers, two guys whose most recent album-release strategy backfired so dramatically that I’m willing to bet plenty of people don’t even realize it happened. Simply put, it’s hard to see what 5SOS had to gain. So, again: why?

You might ask the same question about Coldplay, who two years ago collaborated with the Chainsmokers to produce the inescapable “Something Just Like This”, a thoroughly decent song that features an utterly confused retelling of Greek history. Coldplay, after all, is one of the biggest rock bands of the twenty-first century, who have managed to stay afloat for twenty years in spite of massively changing trends within the music industry, both commercially and creatively. Does a band like that really have any need for two people whose public image is built entirely around one embarrassing interview in Billboard Magazine?

Well: yes and no. While it is true that Coldplay has been around a lot longer than the Chainsmokers, they’ve maintained that longevity partially by collaborating with other artists, whether they be seasoned pop producers like Stargate on “Adventure Of A Lifetime,” or people who were still in middle school when “Yellow” dropped, like Rihanna on “Princess of China” or Avicii on “A Sky Full Of Stars” — the band’s first foray into EDM. In 2016, they even benefited from the residual glow of Beyonce after she provided guest vocals on “Hymn For The Weekend” and mercifully allowed them to stand next to her during the Super Bowl Halftime Show.

With this in mind, we can see the loose outline of how “Something Just Like This” came together: in late 2016, the Chainsmokers had a couple of real hits under their belt, including the massively successful “Closer”, all built around a slick mix of EDM and alternative rock sounds. Coldplay had themselves done decent numbers experimenting with that exact blend of musical styles. Considering it this way, it seems so calculated as to be almost cynical, but hey – you don’t get to where Coldplay is without playing the angles.

But this still leaves one question, the same on that has plagued me for what now feels like untold aeons: why the Chainsmokers? Surely there were other electronic music artists who would be willing to work with a group like Coldplay. Surely Chris Martin and co. would rather lend their name to a more established performer like Calvin Harris, Diplo, Zedd – hell, Avicii had already worked with them twice. Was he just too busy in late 2016 to make time for them? Seriously, Coldplay made a song with Beyonce and didn’t even give her a featured credit, but they were willing to split lead billing with these guys?

I believe there is an answer to this question. But as a wise man once said, to understand the future, we have to go back in time — and in this case, that means going all the way back to 2012, when actress and singer Priyanka Chopra tried to break in to the American music scene.

The average American probably knows about as much about Priyanka Chopra as they do about 5 Seconds Of Summer. They recognize the name, and they might be able to name one or two things either of them have done, but unless they’re well-versed in each artists’ respective genres, they might not realize just how important they are. The difference is, 5SOS are a culturally dominant force within the world of teenage girls and Priyanka Chopra is a culturally dominant force within the world of people who live in India.

In 2000, Chopra was crowned the winner of the Miss World 2000 beauty pageant and parlayed her newfound fame into a career as one of the biggest names in Indian cinema. She’s won awards, she’s started her own charity foundation, she’s hosted the Indian version of Fear Factor, she’s written over fifty columns for the Hindustan Times (circulation 993,645 daily — about double that of the New York Post!), and lest we pass over this fact too quickly, when she was eighteen years old she won an award for being the most attractive woman in the world. Momentarily setting aside the ethical considerations of bestowing this dubious title upon a teenager, we can safely say that Chopra has lived a highly accomplished life.

In 2012, with assistance from her overseas manager and co-founder of DesiHits Universal Anjula Acharia-Bath, Chopra began developing a musical career in the U.S. Her first attempt was an upbeat and cheery pop number called “In My City”, a song co-developed by and featuring the Once And Future Black Eyed Pea, will.i.a.m. This was to be her big crossover moment, and on paper it seemed like as sure thing: one of the era’s most reliable hit-makers teaming up with one of the world’s most popular female entertainers to extol the many joys of being in and/or from a city.

Listening to it now, “In My City” transports me back to that dark period in America’s history where will.i.am held complete sway over the pop charts. For those who weren’t there, let me assure you that it was a truly grisly time. You never knew when will.i.am might strike — you could be innocently enjoying the work of Flo-Rida or Ke$ha or Usher, only for will.i.am to suddenly appear and kill your buzz with an insultingly lazy rap verse. For a brief time, we even entrusted Britney Spears’ entire career to his foul and capricious whims. We should all be punished for that; it is my belief that some day, somehow, we will.

Priyanka Chopra certainly paid the price for putting her trust in will.i.a.m: despite a record-breaking opening week in India and a stateside debut during a primetime slot on something called the NFL Network(?), “In My City” failed to chart in America, netting only 5,000 downloads from the iTunes store in its first week. You can imagine the frustration of Chopra, Acharia-Bath, and all their advocates at Sony Music Group. You only get one chance to make a first impression, after all—and in this case, that impression was a flashy and overtly commercial pop song that completely failed to hit the mark. Twelve years of hard work were jeopardized and a seemingly untapped well of potential for overseas success evaporated in an instant. So, Priyanka Chopra did what anyone in her situation would do: she made a song with the Chainsmokers.

Of course, this was before the idea of “making a song with the Chainsmokers” even existed – in fact, this was about as early as person could possibly have even tried to make a song with the Chainsmokers. Now, the timeline is a little fuzzy here, but based on statements made in various interviews, we can safely say that Alex Pall and Andrew Taggart first began working together as The Chainsmokers in late October or very early November 2012, having been introduced to one another by manager Adam Alpert, future CEO of Disrupter Records (which, like DesiHits, was tightly connected to Sony’s music division). And we can say with no question that their song “Erase”, featuring vocals from Priyanka Chopra, was first released to the internet on November 13, 2012. We know because this was the date it was first posted on the Chainsmokers’ SoundCloud account and, as a matter of fact, it was the first track they ever posted.

I’ve thought about this a lot, more than is healthy for any semi-functioning human adult. I’ve scrolled through pages upon pages of Indian-language culture writing, shoddily translated by my Internet browser, trying to uncover something, anything about the story behind this song. The best lead I’ve come across in all my research is the discovery that Steve Stoute, producer/entrepreneur/author and advisory board member of DesiHits, seeks legal advice from the same team of lawyers as Adam Alpert, the man who created the Chainsmokers as we knew them today. And if anyone from the Chainsmokers’ management team is reading this, please know that all this research was done ironically and therefore does not constitute a breach of privacy or grounds for a cease and desist letter/restraining order.

My theory – and, again, please remember that I have no idea what I’m talking about – is this: after the failure of “In My City”, Chopra and her team realized they couldn’t release another big pop song, so they sought a new approach, one that would allow Chopra to enter the American music scene through a different route. Alpert, learning of this conundrum through some mutual acquaintances, saw an opportunity to boost his new clients and called in a few favors to do so, maybe even sweetening the pot by suggesting that this would be a more interesting, edgy and low-stakes approach to advancing Chopra’s musical career. Go underground, essentially – get into the public consciousness through the clubs. And what could be more underground than working with two guys who have literally never released a song?

This explanation is not perfect. In some ways, it raises further concerns, like: can you really picture this recording session? Drew and Alex, two people who have known each other for all of a week, maybe two, in the studio with Priyanka fucking Chopra, laying down some incredibly tacky synth line for her to sing over – it sounds impossibly surreal. And the question of the timing is so bizarre that it conjures up potential conspiracy theories: did the Chainsmokers even exist before Adam Alpert realized that Chopra had a need they could fill? Is it possible the Chainsmokers were formed for the sole reason of recording and releasing “Erase?” It’s unlikely, but it doesn’t seem that much more unlikely than the alternative.

But in a real way, none of this actually matters. The result is the same: Chopra was a performer who wanted to release a song that was different from her previous work. It’s essentially the exact move that Coldplay made with “Something Just Like This” – the only difference being that Coldplay had fifteen years of music behind them while Chopra had about two months. The same can even be said of 5SOS. “Who Do You Love” is the most overtly pop-centric song they’ve ever recorded. They don’t want to be a pop band any more than Coldplay wanted to be an EDM band or Priyanka Chopra wanted to be the modern-day Do. All these people wanted to step outside of their established musical domain without sacrificing their core identity, so they made a song that didn’t really count as “theirs” — after all, this was a song by the Chainsmokers, so if people didn’t like it, the featured artist had plausible deniability.

This strategy doesn’t always work out the same way: Coldplay kept themselves relevant for another year, while Priyanka Chopra’s big break in America eventually came in the form of the TV show Quantico — although she did release a few more singles, including one pretty good collaboration with Pitbull. It still remains to be seen how “Who Do You Love” will impact 5SOS’s career, but as for the Chainsmokers, it’s already charting better than most of the the stuff that they put out last year. It is also, for what it’s worth, an impossibly catchy song that I like more than anything else I’ve heard from 5 Seconds Of Summer. But in the end, what matters is that everyone involved got what they wanted: to try something new without putting their own identity at stake — to protect their brand. And really, what more can any of us ask for?

Oh, I don’t know, maybe a plan to address climate change that actually sets goals and outlines a course of action instead of whatever non-binding half-measure that Chuck Schumer and the rest of the Democratic leadership are currently planning to introduce?

Alright — that was the last one.